Author: Theocharidou Christina Chrysanthi 1a, Vagiana Evdoxia 2b, Athanasiadou Anastasia3a, Endiaroglou Melanthi3a, Ampatzıdou Fotini1a*

1MD, MSc, Intensive Care Unit

2MD, MSc, RN, Intensive Care Unit

3MD, Intensive Care Unit

aC΄ Intensive Care Unit, General Hospital, “G. Papanikolaou”, Thessaloniki, Greece

bΑ΄ Intensive Care Unit, General Hospital, “G. Papanikolaou”, Thessaloniki, Greece

*Correspondence: C΄ Intensive Care Unit, General Hospital, “G. Papanikolaou”, Leoforos Papanikolaou, Exohi, Thessaloniki, Greece, Tel: 00302313307000, e-mail:

ABSTRACT

Tracheal tumors are rare neoplasms that can present with symptoms mimicking more common respiratory conditions, such as asthma. We report a case of a 71-year-old male who presented to the emergency department with severe respiratory distress initially diagnosed as status asthmaticus. Despite aggressive conventional asthma therapy, the patient remained in respiratory failure requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. Further investigation with computed tomography and bronchoscopy revealed a tracheal mass later confirmed as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis when evaluating elderly patients with apparent new-onset asthma in the emergency setting. Emergency physicians should consider central airway obstruction, including tracheal malignancy, in patients with atypical presentations of common respiratory conditions or those failing to respond to conventional treatment. Early recognition is crucial for improving outcomes in these challenging cases.

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory distress is one of the most common presenting complaints in emergency departments worldwide, with asthma exacerbations representing a significant proportion of these cases. The emergency physician’s initial decisions can significantly impact patient outcomes, particularly in cases of severe airway compromise. However, diagnostic challenges arise when symptoms mimic common conditions but stem from rare underlying pathologies1.

Tracheal tumors, with an incidence of approximately 0.1 per 100,000 population, represent a rare cause of central airway obstruction that can present with wheezing and dyspnea similar to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)2. Primary malignant tumors of the trachea account for less than 0.2% of all respiratory tract malignancies, with squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma being the most common histological types, while adenocarcinoma is considerably rarer3. The nonspecific nature of symptoms often leads to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment, significantly affecting prognosis4.

The emergency setting presents challenges in identifying these rare conditions, as the initial focus is often on rapid stabilization and treatment of presumed common causes of respiratory distress. In this report, we present a case of tracheal adenocarcinoma initially presenting as apparent status asthmaticus, highlighting the critical decision points that emergency physicians may encounter when facing similar clinical scenarios.

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old male ex-smoker with a 40 pack-year smoking history presented to the emergency department with acute, severe shortness of breath that had progressively worsened over two weeks. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and hyperlipidemia, with no prior established diagnosis of asthma, COPD, or other chronic respiratory conditions. He reported having completed a one-week course of amoxicillin/clavulanate prescribed by his primary care physician for suspected respiratory tract infection, without improvement.

On arrival to the emergency department, the patient appeared in severe respiratory distress, leaning forward in a tripod position, using accessory muscles. Vital signs revealed tachypnea (respiratory rate 32/min), tachycardia (heart rate 118/min), blood pressure 146/88 mmHg, temperature 37.2°C, and severe hypoxemia with oxygen saturation of 79% on room air. Physical examination demonstrated diffuse wheezing bilaterally with prolonged expiratory phase and markedly decreased air entry.

Initial management included administration of high-flow oxygen via non-rebreather mask, inhaled salbutamol and ipratropium bromide via nebulizer, and intravenous hydrocortisone (200 mg). Despite these interventions, the patient’s respiratory status continued to deteriorate rapidly. Arterial blood gas analysis on a non-rebreather mask revealed severe respiratory acidosis (pH 7.18, pCO2 69 mmHg, pO2 48 mmHg, HCO3– 24 mmol/L), indicating severe respiratory failure.

Given the patient’s critical condition, the emergency physician proceeded with rapid sequence intubation using ketamine and rocuronium. Post-intubation, mechanical ventilation was challenging due to high airway pressures and persistent wheezing despite deep sedation. Additional therapeutic measures included continuous nebulized beta-agonists, inhaled adrenaline, intravenous magnesium sulfate, and increased doses of corticosteroids, all without significant improvement.

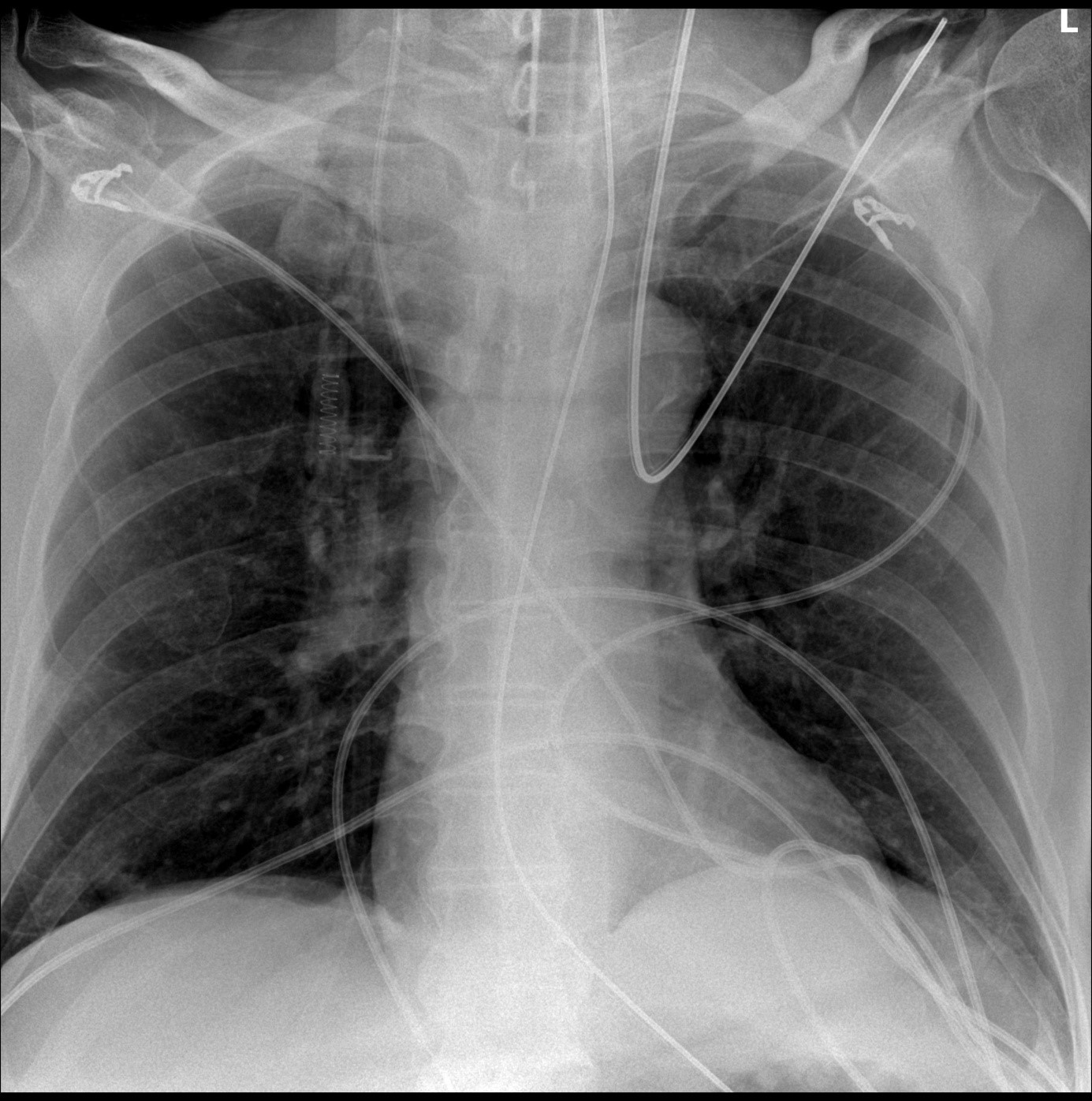

Laboratory investigations revealed a white blood cell count of 9.8 × 10^9/L with normal differential, hemoglobin 13.6 g/dL, platelet count 245 × 10^9/L, and normal renal and liver function tests. Chest radiography performed in the emergency department after intubation showed no obvious infiltrates, masses, or pleural effusions (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Chest radiography of a 71-year-old man presenting with refractory bronchospasm to the emergency department.

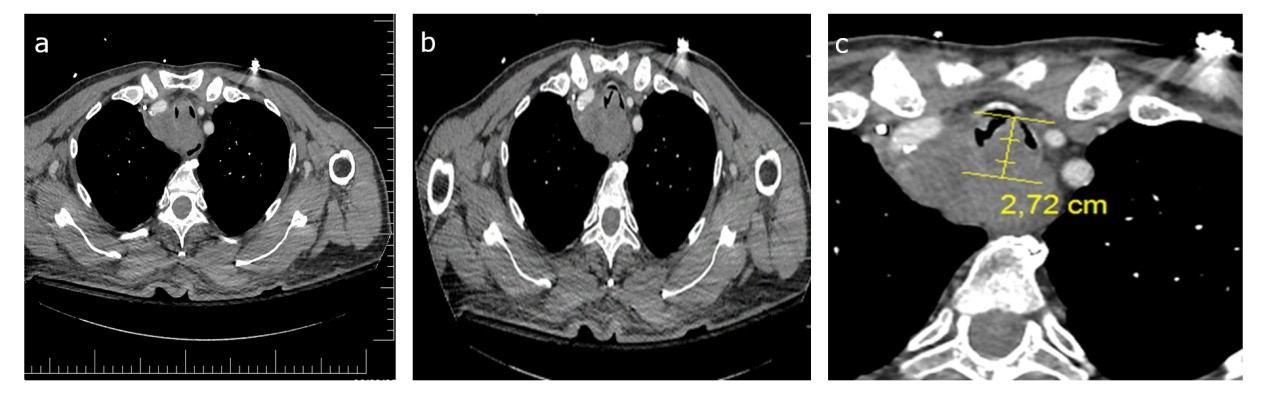

Due to the refractory nature of the presumed asthma exacerbation in an elderly patient with no prior history of asthma, the emergency physician consulted with the intensive care and pulmonology teams and decided to pursue additional imaging. An urgent computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and chest with pulmonary angiography was performed, which revealed a mass in the upper mediastinum invading the posterior wall of the trachea causing significant obstruction (Fig 2). Additionally, a right lung infiltrate with radial projections affecting the lateral aspect of the middle lobe was noted, suspicious for malignant spread. No pulmonary embolism was identified.

Figure 2. Computed tomography images of the thorax (axial views): Sequential cuts demonstrating a) and b) mass arising from the posterior wall of the trachea, and c) mass measurement showing maximal diameter of 2.72 cm causing significant airway obstruction.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with a revised diagnosis of airway obstruction due to suspected malignancy. The bronchospasm remained refractory to bronchodilators and corticosteroids, necessitating continuous administration of a neuromuscular blocking agent (cisatracurium) for adequate ventilation and oxygenation. The ventilator strategy was modified to accommodate the central airway obstruction, with lower tidal volumes, longer expiratory times, and permissive hypercapnia.

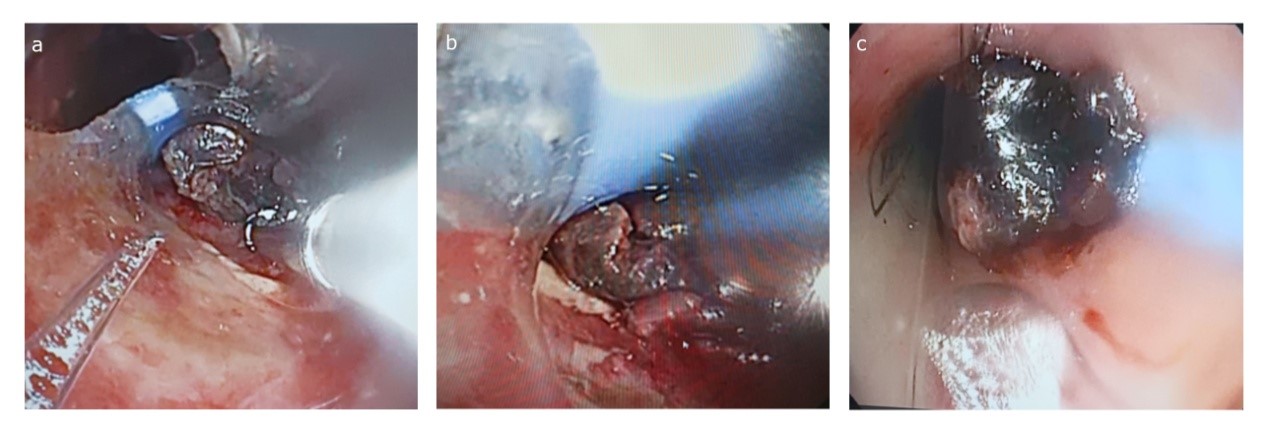

On the second day of hospitalization, fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed, which confirmed an obstructive mass arising from the posterior tracheal wall approximately 4 cm below the vocal cords (Fig 3). The mass appeared friable with areas of necrosis. Attempts at endobronchial biopsy with forceps provided insufficient tissue for diagnosis and were complicated by moderate bleeding requiring local epinephrine application for hemostasis and repeated bronchoscopy to remove clots.

Given the challenges in obtaining adequate tissue via bronchoscopy, the cardiothoracic surgery team was consulted and performed a mediastinoscopy. Tissue samples were obtained, and histopathological examination revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of tracheal origin with extensive invasion into surrounding mediastinal structures.

A multidisciplinary tumor board discussion concluded that the extent of local invasion and suspected metastatic disease precluded curative surgical resection. Palliative measures, including consideration for tracheal stenting and radiation therapy, were planned. However, despite maximal supportive care, the patient developed progressive respiratory failure and multiorgan dysfunction. After discussion with the family regarding poor prognosis, a decision was made to transition to comfort care, and the patient expired after fourteen days of hospitalization. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s next of kin for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Figure 3. Sequential bronchoscopy views: a) Initial visualization through the endotracheal tube with friable tumor tissue visible at the distal end, b) Closer view revealing an irregular mass, and c) Close-up view demonstrating near-complete tracheal obstruction by the tumor mass.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights several important considerations and learning points for emergency physicians encountering patients with severe respiratory distress. The initial presentation mimicked a severe asthma exacerbation or status asthmaticus, a common emergency department diagnosis. However, certain features warranted additional consideration and investigation.

First, the presentation of new-onset, severe “asthma” in an elderly patient with no prior history of asthma or atopy should raise suspicion for alternative diagnoses. While asthma can develop at any age, true late-onset asthma in the elderly has distinct phenotypic features and often a different clinical course compared to asthma developing earlier in life5.

The incidence of new-onset asthma declines after age 65, making other etiologies more likely when elderly patients present with new wheezing.

Second, poor response to conventional therapies for asthma should prompt immediate consideration of alternative diagnoses. In our case, the patient demonstrated no improvement despite receiving maximal bronchodilator therapy, intravenous corticosteroids, and adjunctive treatments. This refractory nature should alert the emergency physician to look beyond the initial diagnosis. Therapeutic response can serve as an important diagnostic clue, with true asthma typically showing at least partial response to appropriate therapy6.Third, the initial normal chest radiograph demonstrates the limitations of conventional imaging in detecting central airway pathology. This case underscores the value of early advanced imaging, particularly CT scans, in evaluating unexplained or refractory respiratory distress. Emergency physicians should have a low threshold for obtaining such imaging when clinical presentation and treatment response do not align with the presumed diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for wheezing in adults includes common conditions such as asthma, COPD exacerbation, and heart failure, as well as less common etiologies such as vocal cord dysfunction, foreign body aspiration, anaphylaxis, and central airway obstruction from various causes. Tracheal tumors, though rare, should be considered particularly in patients with risk factors such as smoking history, age over 60 years, and atypical presentation or treatment response. Adenocarcinoma of the trachea, as seen in our case, represents less than 5% of all primary tracheal malignancies and carries a poor prognosis, particularly when diagnosed at an advanced stage with extensive local invasion or metastasis7.

The diagnostic approach to suspected tracheal tumors typically involves a combination of imaging and endoscopic evaluation. Computed tomography provides detailed information about the location, size, and extent of the tumor, involvement of surrounding structures, and potential metastatic disease. Bronchoscopy allows direct visualization of the lesion and tissue sampling for histopathological diagnosis. However, as demonstrated in our case, obtaining adequate tissue can be challenging due to the location of the tumor and risk of bleeding, sometimes necessitating more invasive surgical approaches such as mediastinoscopy.

Treatment options for tracheal tumors depend on histological type, location, and extent of disease, and typically involve a multidiscipli-nary approach.

For localized disease, surgical resection with primary reconstruction offers the best chance for cure. Other modalities include endoscopic resection, laser therapy, stenting for airway patency, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy8. In advanced cases with extensive invasion, as in our patient, palliative approaches focusing on maintaining airway patency and symptom control may be the only feasible options, as prognosis is extremely poor9.

From an emergency medicine perspective, this case emphasizes the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis and recognizing when a patient’s presentation or response to therapy does not fit the presumed diagnosis. Emergency physicians should be familiar with the various causes of central airway obstruction and have a low threshold for advanced imaging and specialist consultation when encountering patients with atypical or refractory respiratory symptoms.

CONCLUSION

This case of tracheal adenocarcinoma masquerading as status asthmaticus highlights three key learning points for emergency physicians: (1) Consider alternative diagnoses in elderly patients with apparent new-onset asthma, particularly when severe and refractory to standard therapy; (2) Obtain advanced imaging promptly when bronchospasm fails to respond to conventional treatment; and (3) Pursue diagnostic persistence through specialist consultation when clinical suspicion remains high despite initial inconclusive results. Recognizing atypical features or treatment responses and initiating appropriate diagnostic workup can significantly impact patient outcomes. This case serves as a reminder that “not all that wheezes is asthma,” particularly in the elderly population presenting to the emergency department with new-onset respiratory symptoms.

Addittional materials: No

Acknowledgements: Not applicable

Authors’ contributions: Th Ch Ch drafted the paper and is the lead author. VE contributed to planning and the critical revision of the paper. AA contributed to planning and the critical revision of the paper. EM contributed to planning and the critical revision of the paper. AF contributed to planning and the critical revision of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate: No IRB approval required.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Received: June 2025, Accepted: July 2025, Published: September 2025.

REFERENCES

- Kann K, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical mimics: an emergency medicine–focused review of asthma mimics. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(2):195-201. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed. 2017.01.005

- Marwah V, Katoch CDS, Garg Y, Pathak K, Kakria N. Primary tracheal schwannoma masquerading as bronchial asthma: a case report and review of literature. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2022;61(1):43-45. doi:10.5005/ijcdas-61-1-43

- Wu CC, Shepard JAO. Tracheal and airway neoplasms. Semin Roentgenol. 2013;48(4): 354-364. doi:10.1053/j.ro.2013. 03.018

- Honings J, Gaissert HA, Van Der Heijden HFM, Verhagen AFTM, Kaanders JHAM, Marres HAM. Clinical aspects and treatment of primary tracheal malignancies. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130(7):763-772. doi:10.3109/ 00016480903403005

- Dunn RM, Busse PJ, Wechsler ME. Asthma in the elderly and late‐onset adult asthma. Allergy. 2018;73(2):284-294. doi:10.1111/all. 13258

- Quirce S, Heffler E, Nenasheva N, et al. Revisiting late-onset asthma: clinical characteristics and association with allergy. J Asthma Allergy. 2020;Volume 13:743-752. doi:10.2147/JAA.S282205

- Bhattacharyya N. Contemporary staging and prognosis for primary tracheal malignancies: a population‐based analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(5):639-642. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.05.018

- Piórek A, Płużański A, Winiarczyk K, et al. Tracheal cancers. Oncol Clin Pract. 2024;20(1):52-59. doi:10.5603/ocp.97601

- Theodore PR. Emergent management of malignancy-related acute airway obstruction. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27(2):231-241.doi:10.1016/j.emc.2009.01.009

Publisher’s Note

The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional afliations.

| Citation: Theocharidou Ch. Ch, Vagiana E, Athanasiadou A, Endiaroglou M, Ampatzidou F. Tracheal Adenocarcinoma asquerading as Status Asthmaticus: Α Case Report. Greek e j Perioper Med. 2025;24 (b): 49-56. |